|

| Alex Schadenberg |

International Chair, Euthanasia Prevention Coalition

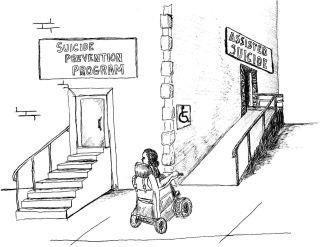

Last week Peter Singer, the bioethicist from Princeton University debated Anthony Fisher the Archbishop of Sydney Australia. Singer, who has published books supporting euthanasia, assisted suicide and infanticide, faced strong criticism from the disability rights community.

Today, Craig Wallace, the convenor of Lives Worth Living, a disability advocacy group speaking out about euthanasia and eugenics, and is the president of People with Disability Australia (PWDA), was published by Crickey with an article explaining why the disability rights movement opposes Singer's philosophy and why they oppose euthanasia and assisted suicide.

|

| Craig Wallace speaking to the media |

If proponents of voluntary euthanasia were looking to reassure us that legalised suicide would, in fact, be voluntary and not about people with disabilities, they chose the wrong standard bearer. Singer is consistently on the record supporting infanticide of babies with certain disabilities. In his book Practical Ethics, Singer argues the case for selective infanticide. He believes it unfair that:

“At present parents can choose to keep or destroy their disabled offspring only if the disability happens to be detected during pregnancy. There is no logical basis for restricting parents’ choice to these particular disabilities. If disabled newborn infants were not regarded as having a right to life until, say, a week or a month after birth it would allow parents, in consultation with their doctors, to choose on the basis of far greater knowledge of the infant’s condition than is possible before birth.”

Singer may not be “poised, needle in hand” ready to plunge it into the arm of the nearest disabled person. It is, nonetheless, difficult to stick to topic when a person who thinks it might have been a good idea to “destroy” you as a child offers you a whisky shot glass and a pistol in latter days. Forgive us for having trust issues.

Wallace challenges the euthanasia lobby that if euthanasia is mean't to be truly voluntary and not about disability, why don't they define the laws in that way?

If euthanasia is truly only about forestalling the excruciating final hours of people with conditions like end-stage cancer, then why not list the illnesses that are covered in clear diagnostic terms

Because euthanasia legislation consistently defines eligibility through terms like “terminal or irremediable illnesses” the extent of coverage remains opaque.

When does a condition become terminal, exactly? Most medical practitioners would say that a disability like mine shortens the lifespan. There is no clearly defined boundary between a shortened life span and a terminal illness.

When is a condition “irremediable”? Many disabilities are permanent and a person might be unable to move, eat, walk or shower without the support of another person. I know many people with disabilities that look like this. And, at the time they acquired their disabilities, they have told me they want to die.

Wallace explains that his opposition to euthanasia is not based on a religious belief but rather societal attitudes towards people with disabilities.

I oppose introducing euthanasia in a toxic climate. Much of the discourse around disability positions us as better off dead. You do not have to look hard to find people advocating involuntary sterilisation and minimising parental homicides of people with disabilities. You also do not have to look hard to find stories — including on the front pages of daily newspapers — that label all of us as slackers and a drain on society.

|

| Liz Carr |

Well, life gets better for many people with disabilities, too. And that happens when we remove abuse, end discrimination, eliminate access barriers and receive the right supports. Commenting on the recent debate on legislation before Parliament in the United Kingdom, Silent Witness actress and disability campaigner Liz Carr put it well when she said that “what disabled people need is an assisted living, not an assisted dying bill”.

For some of us in Australia, the assisted living part needs to get a lot better. Australia is still at the early stages of implementing a National Disability Insurance Scheme, which will provide the most basic help to hundreds of thousands of people with disability, up until now denied any kind of support.

As Stella Young put it: conversations about dying with dignity are important. But we must first ensure we’re all able to live with dignity.

Previous articles by Craig Wallace:

No comments:

Post a Comment