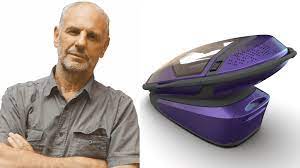

Alex Schadenberg

Executive Director, Euthanasia Prevention Coalition.

|

Dr Harvey Chochinov

|

Dr Harvey Chochinov is a leading Canadian medical researcher who is known for his studies on the Will to Live and the development of Dignity Therapy to ensure a true death with dignity. The Euthanasia Prevention Coalition recognizes the importance of Dignity Therapy.

On February 25, Chochinov wrote a paradigm shifting article that was published as a guest editorial in the Journal of Palliative Medicine titled: The Platinum Rule: A New Standard for Patient-Centred Care.

In his article Chochinov suggests that The Platinum Rule, which would have us consider doing unto patients as they would want done unto themselves, may be a more appropriate standard for achieving optimal person-centered care than the Golden Rule.

Chochinov provides this story to illustrate his point:

Bert was a kind 74-year-old happily married gentleman and father of

five children. He had smoked cigarettes for a few decades, but had quit

years ago, yet had presented with a cancer in his mouth. He underwent a

large surgery that left him hoarse and disfigured. He was unable to

swallow and depended on a gastrostomy tube for his feedings.

Chemotherapy and radiation took their turns in causing more difficulties

with nausea and some painful radiation effects.

Eventually the

cancer recurred. More chemotherapy did not affect the tumor, and

radiation was given with palliative intent. He began to have more pain,

and at that point, one of his oncologists sat down with him and his wife

and told them that he likely had little time to live, that his tumor

was most likely going to progress quickly, and that his last days would

become much more difficult, with increasing pain. The oncologist

suggested that he might consider Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD), to

avoid what was sure to be a time of significant suffering.

Bert

and his wife were a religious couple who had relied on prayer and the

community around them to get them through over the years. They could not

agree to MAiD. It was just not on their list of potential options. When

he met with the palliative care consultant, he was having increasing

pain, which was felt to have a large neuropathic component. A mix of

gabapentin and small doses of methadone helped to reduce his pain to a

very manageable level. The addition of immunotherapy by another

oncologist resulted in a surprisingly good outcome, and now six months

later, although still depending on gastrostomy feedings, he is

frequently out in the garden, watering and weeding, and hoping to take

part in harvest. He recently indicated his quality of life was excellent

(C. Woelk, pers. comm.).

Bert was offered MAiD (euthanasia) because the physician percieved his quality of life to be poor, that Bert was better off dying than suffering or even attempting to find a way to keep Bert comfortable in his remaining days.

Chochinov explains how the Golden Rule may have weaknesses in our ethically diverse culture:

The Golden Rule—do unto others as you would have them do unto you—conveys

deep wisdom, which can be found in some form in many religious and

ethical traditions. In medicine this means treating patients and

families the way we would want to be treated or would want our loved

ones to be treated in similar circumstances. The Golden Rule is based on

the idea of reciprocity and being able to see ourselves in others. If

I were that patient, how would I want to be treated? What if this was

my spouse, my child, my parent or sibling, how would I want them to be

treated? In most instances adherence to The Golden Rule leads to

health care decisions and clinical attitudes that are compassionate and

embrace the essence of person-centered care.

The Golden Rule,

however, has its limitations, as it requires some overlap between how we

see ourselves and how others see themselves. So long as the patient's

values and priorities align with our own, we can infer their needs based

on how we would want to be treated in their situation. The more our

worldview and lived experience deviates from theirs, the more the Golden

Rule begins to unravel. How would I want to be treated it I were

that old? If I were that dependent? Or that disabled, disfigured,

marginalized, or disease ridden? Our own biases and perceptions of

current, and the possibility of future, suffering can lead to attitudes

that are tone deaf and decisions that are discordant with patients'

perceptions, values, and goals.

Chochinov continues by recognizing how the perceptions of the medical team will affect the patient.

Unconscious bias can influence the way we process patient information,

affecting our behavior, interactions, and decision making.

A sense of therapeutic nihilism and clinical passivity can set in, a

feeling that nothing is worth trying and certain lives may not be worth

preserving, leading us to withhold treatment, perhaps forgo diagnostic

tests and let nature take its course. Inferring we would not want

to live this way, distorted compassion—that is compassion based on

tainted or inaccurate perceptions of another person's suffering—can lead

to ostensibly well-intended advice, actions, or inactions that may be

completely at odds with what the patient really wants. Rather than

feeling that they have been heard, distorted compassion can result in

patients feeling devalued, misunderstood, and further demoralized at the

very hands of those who are meant to help.

|

Catherine Frazee

|

To provide greater clarity, Chochinov quotes disability rights advocate Catherine Frazee:

Catherine Frazee, a pre-eminent disability rights advocate, who lives

with spinal muscular atrophy says, “having to wear diapers and drooling

are highly stigmatized departures from what is expected of adult bodies.

Those of us who deviate from these norms experience social shame and

stigma that erodes resilience and increases vulnerably. The more deeply

these stigmatized accounts are embedded in our discourse and social

policy, the more deeply virulent social prejudice takes hold within our

culture.

Chochinov then explains how the Platinum rule leads to better patient care. He writes:

The Platinum Rule, which would have us consider—doing unto patients as they would want done unto themselves—offers

a standard that is more likely to result in treatment decisions that

are consistent with patients' personal needs and objectives. Doing unto

as per the Platinum Rule implicates not only clinical decisions, but

treating patients—as in acting toward them—as they would want to be

treated. This means establishing a care tenor that is informed by asking

what we need to know about them as a person to take the best care of

them possible.

Chochinov concludes by referring back to his Bert's story:

...one can easily imagine Bert's

physician recommending MAiD from a position of wanting to mitigate

current and future suffering. One can also easily imagine, based on the

Golden Rule, that he offered a solution for a clinical situation he

could neither fathom himself nor those he loved being able to bear.

Distorted compassion, however, represents a failure of the imagination.

Perceptions of suffering can obstruct our ability to imagine patients

experiencing life as having sustained meaning, purpose, and value,

despite even overwhelming challenges. The Golden Rule has its place in

medicine, given it provides an initial gauge in our response to patient

suffering. But if we are truly intent on offering patient-centered care,

consistent with their values, preferences, and goals, consideration of the Platinum Rule is required: doing unto patients as they would want done unto themselves.

More articles related to Dr Harvey Chochinov (Link).