|

| Andrew Coyne |

The case for assisted suicide and euthanasia, at least as it has been presented, is that we may freely dispense with certain moral distinctions, once considered of some importance — between killing yourself and having someone else kill you; between refraining from prolonging life and deliberately ending it — while continuing to insist on any number of others.

The issue is thus invariably cast as if the practice would be reserved for adults of sound mind, in the final stages of a terminal illness, suffering unbearable physical pain, freely consenting to have done to them what they would surely choose to do themselves were they not so disabled. In its most complete form, the patient must not only consent, but actually initiate the process in some way (hence “assisted” suicide, versus euthanasia, where someone else does the deed). At all events we are assured the task would be performed by a licensed physician, no doubt with a sterilized needle.

So it is that a cause advanced in the name of a limitless individual freedom (self-annihilation, it is said, being the ultimate assertion of personal autonomy) defends itself with reference to how acutely limited that freedom would actually be. Advocates, impatient with such arbitrary distinctions as that between suicide and assisted suicide — of what use is the right to kill oneself, they ask, if you are physically incapable of carrying it out? — are nevertheless at pains to preserve the distinction between terminal illness and mere depression, between adults and children, between the mentally competent and incompetent, between personally consenting and having someone else consent on your behalf.

But it cannot be. By erasing the one distinction, they eviscerate the rest. For the right asserted in this case is not merely a negative right, in the old-fashioned sense of the right to be left alone, but a positive right, a claim on others, entitling one to their assistance. It is not a civil liberty, such as the right to vote, implying a degree of competency or at least free will such that it might justifiably be restricted to adults, but a more fundamental sort of right, like the right not to be tortured, that does not hinge upon agency in the rights-holders, but inheres in them simply as human beings (or even animals).

That is the implication of erasing the line between suicide and assisted suicide. When we say the former right is of “no use” to certain people, we are saying the mere absence of legal restraint is insufficient. We are not merely upholding their freedom to choose that option. We are saying that option should in fact be made available to them. We are not just establishing a right to what was previously forbidden: we are changing how we think of the act itself — of suicide, from a tragedy to a benefit, a release from suffering; of assisting suicide, from a crime into a service. We are asserting that helping people in pain to end their lives — killing them, to be more direct — is a positive good, which it is the state’s obligation not merely to tolerate, but to facilitate.

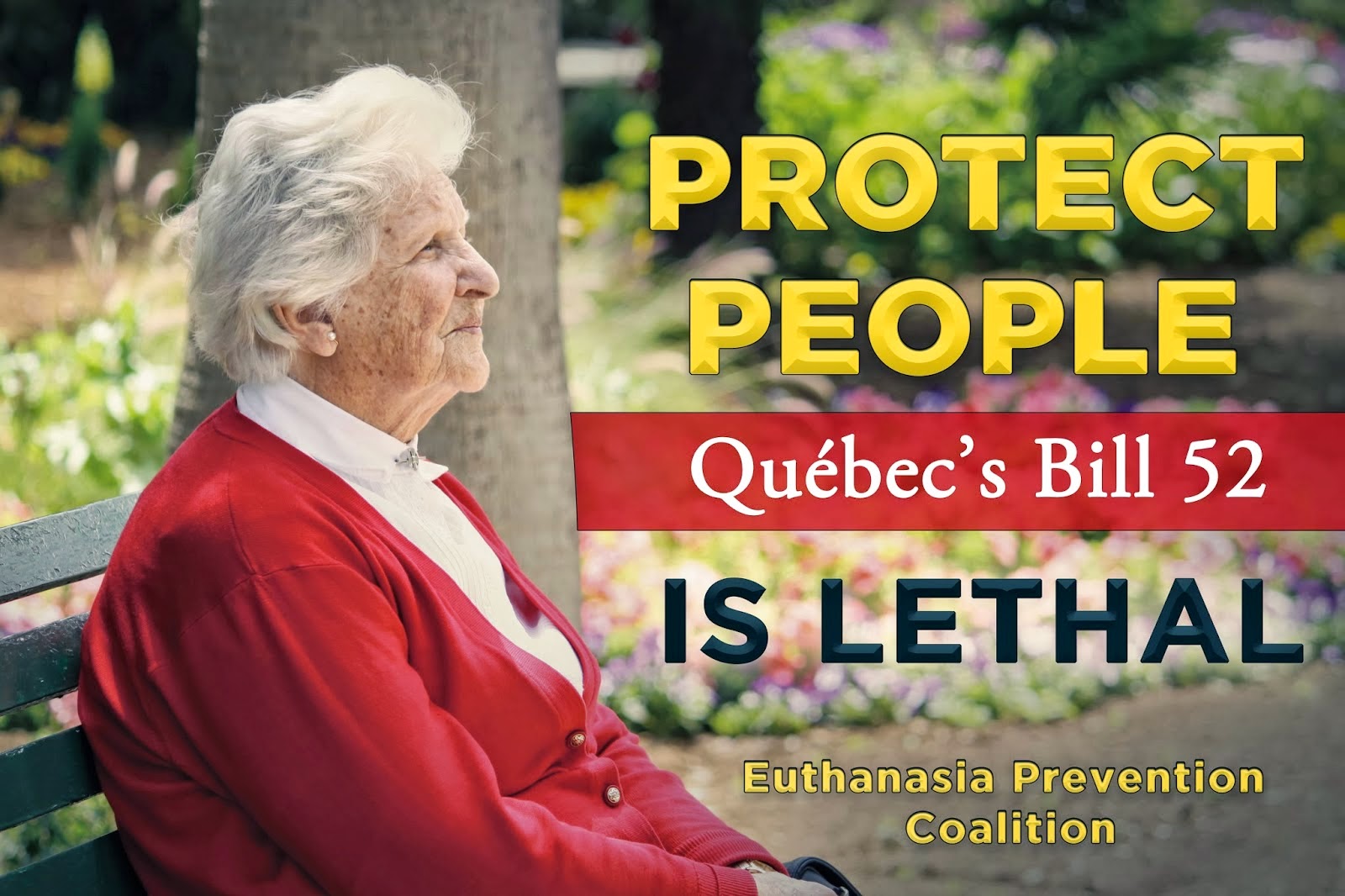

Quebec’s Bill 52, for example, passed earlier this year, does not merely legalize euthanasia (or “medical aid in dying”) but requires all hospitals and nursing homes to offer it as a service, “in continuity and complementarity with any other care that is or has been provided to them.” Doctors who agree to participate must administer the lethal dose themselves; those who refuse to kill those in their care must see that a patient who requests it is referred to a more obliging physician. Needless to say, the service will be offered at public expense, though only to those with a valid Quebec health card.

To be sure, the Quebec bill has all of the usual riders about patients being “at the end of life,” of sound mind, in unbearable pain, and such. But the pain doesn’t have to be physical: “psychological suffering” will do. And the patient doesn’t actually have to be terminally ill or incapable of killing himself: just in “an advanced state of irreversible decline.” Likewise, Bill S-225, lately introduced in the Senate, while it would impose a 14-day waiting period and require the approval of two doctors, is not confined to those with a terminal illness. So already the constraints are being loosened, the original justifications discarded.

How could they not? Indeed, if the case for assisted suicide is not rooted in personal freedom but quality of life concerns, it is impossible to see how any of the purported restrictions could remain. Are we really prepared to condemn a child to unbearable suffering, when we would not an adult? Are the mentally incompetent any less entitled to such relief, merely because they are incapable of giving consent? This is not some vague anxiety about slippery slopes. It is the logical implication of its own stated premises.

Indeed, some of its most prominent advocates are on the record demanding exactly that. Udo Schuklenk, professor of bioethics at Queen’s University and chair of the Royal Society of Canada’s panel on “End of Life Decision Making,” recently published a paper advocating the euthanizing, with parents’ consent, of infants with severe deformities, a practice he likened to “post-natal abortion.” Eike-Henner Kluge, former director of ethics for the Canadian Medical Association, has made similar arguments for including the mentally incompetent among those eligible for euthanization.

This is hardly a theoretical concern. In countries where assisted suicide/euthanasia has been legalized, it is increasingly the practice. Belgium, where euthanasia on the Quebec model has been legal since 2002, this year extended it to children, joining the Netherlands, where it has been lawful since the 1990s. In Switzerland it is permitted to euthanize the mentally ill. And the list continues to grow: prisoners serving life sentences are the latest addition. What begins in compassion, it seems, ends in eugenics.

The issue is thus invariably cast as if the practice would be reserved for adults of sound mind, in the final stages of a terminal illness, suffering unbearable physical pain, freely consenting to have done to them what they would surely choose to do themselves were they not so disabled. In its most complete form, the patient must not only consent, but actually initiate the process in some way (hence “assisted” suicide, versus euthanasia, where someone else does the deed). At all events we are assured the task would be performed by a licensed physician, no doubt with a sterilized needle.

So it is that a cause advanced in the name of a limitless individual freedom (self-annihilation, it is said, being the ultimate assertion of personal autonomy) defends itself with reference to how acutely limited that freedom would actually be. Advocates, impatient with such arbitrary distinctions as that between suicide and assisted suicide — of what use is the right to kill oneself, they ask, if you are physically incapable of carrying it out? — are nevertheless at pains to preserve the distinction between terminal illness and mere depression, between adults and children, between the mentally competent and incompetent, between personally consenting and having someone else consent on your behalf.

But it cannot be. By erasing the one distinction, they eviscerate the rest. For the right asserted in this case is not merely a negative right, in the old-fashioned sense of the right to be left alone, but a positive right, a claim on others, entitling one to their assistance. It is not a civil liberty, such as the right to vote, implying a degree of competency or at least free will such that it might justifiably be restricted to adults, but a more fundamental sort of right, like the right not to be tortured, that does not hinge upon agency in the rights-holders, but inheres in them simply as human beings (or even animals).

That is the implication of erasing the line between suicide and assisted suicide. When we say the former right is of “no use” to certain people, we are saying the mere absence of legal restraint is insufficient. We are not merely upholding their freedom to choose that option. We are saying that option should in fact be made available to them. We are not just establishing a right to what was previously forbidden: we are changing how we think of the act itself — of suicide, from a tragedy to a benefit, a release from suffering; of assisting suicide, from a crime into a service. We are asserting that helping people in pain to end their lives — killing them, to be more direct — is a positive good, which it is the state’s obligation not merely to tolerate, but to facilitate.

Quebec’s Bill 52, for example, passed earlier this year, does not merely legalize euthanasia (or “medical aid in dying”) but requires all hospitals and nursing homes to offer it as a service, “in continuity and complementarity with any other care that is or has been provided to them.” Doctors who agree to participate must administer the lethal dose themselves; those who refuse to kill those in their care must see that a patient who requests it is referred to a more obliging physician. Needless to say, the service will be offered at public expense, though only to those with a valid Quebec health card.

To be sure, the Quebec bill has all of the usual riders about patients being “at the end of life,” of sound mind, in unbearable pain, and such. But the pain doesn’t have to be physical: “psychological suffering” will do. And the patient doesn’t actually have to be terminally ill or incapable of killing himself: just in “an advanced state of irreversible decline.” Likewise, Bill S-225, lately introduced in the Senate, while it would impose a 14-day waiting period and require the approval of two doctors, is not confined to those with a terminal illness. So already the constraints are being loosened, the original justifications discarded.

How could they not? Indeed, if the case for assisted suicide is not rooted in personal freedom but quality of life concerns, it is impossible to see how any of the purported restrictions could remain. Are we really prepared to condemn a child to unbearable suffering, when we would not an adult? Are the mentally incompetent any less entitled to such relief, merely because they are incapable of giving consent? This is not some vague anxiety about slippery slopes. It is the logical implication of its own stated premises.

Indeed, some of its most prominent advocates are on the record demanding exactly that. Udo Schuklenk, professor of bioethics at Queen’s University and chair of the Royal Society of Canada’s panel on “End of Life Decision Making,” recently published a paper advocating the euthanizing, with parents’ consent, of infants with severe deformities, a practice he likened to “post-natal abortion.” Eike-Henner Kluge, former director of ethics for the Canadian Medical Association, has made similar arguments for including the mentally incompetent among those eligible for euthanization.

This is hardly a theoretical concern. In countries where assisted suicide/euthanasia has been legalized, it is increasingly the practice. Belgium, where euthanasia on the Quebec model has been legal since 2002, this year extended it to children, joining the Netherlands, where it has been lawful since the 1990s. In Switzerland it is permitted to euthanize the mentally ill. And the list continues to grow: prisoners serving life sentences are the latest addition. What begins in compassion, it seems, ends in eugenics.

Links to more articles on this topic:

- A critique of Canadian Senate Bill S - 225 - An Act to Amend the Criminal Code (physician-assisted death).

- Canadian Senate to debate dangerous euthanasia bill.

- Legalizing euthanasia and assisted suicide is not safe. Patient safety must come first.

- Death is not preferable to living with a significant disability.

- Why I'm afraid of Stephen Fletcher's assisted suicide bill.

No comments:

Post a Comment