Alex Schadenberg

Executive Director, Euthanasia Prevention Coalition

|

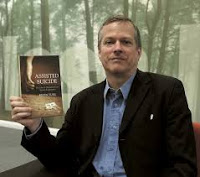

| Kevin Yuill |

Yuill begins his article by quoting Baroness Meacher who recently introduced an assisted suicide measure in the House of Lords (UK) that was thankfully defeated. Yuill begins his article by examining Meacher's statement with helping a friend arrange an assisted death in Switzerland:

‘I was motivated purely by compassion. But in the eyes of the law, my acts made me a criminal.’Yuill responds to Meacher's statement by writing:

Although it looks reasonable and humane, this campaign to legalise assisted dying is anything but. As I will set out below, it is primarily based on fear-mongering; it would undermine the idea of moral equality that regards the killing of an 86-year-old as just as wicked as the killing of a 24-year-old; and rather than liberate the individual, it would destroy his freedom.Yuill then deals with the issue of the changing terminology. He first defines euthanasia and assisted suicide, as they have been traditionally understood and then he states:

Moreover, as the history of the euthanasia movement shows, the undoubtedly genuine compassion of today’s assisted-dying campaigners conceals the disturbing utilitarian and technical view of humanity on which their campaign is ultimately based.

Indeed, the terminology shifts according to timespan and geography. Little wonder, the terms du jour, ‘assisted dying’ and MAiD become blurrier the closer you look at them. MAiD implies assisted suicide in the United States but in Canada all but a handful of MAiD deaths are euthanasia rather than assisted suicide. The Netherlands, where both euthanasia and assisted suicide are legal, has no qualms about using the term suicide – which is considered offensive in the Anglosphere – in order to distinguish them.Yuill then writes about the fear-mongering campaign by the assisted suicide lobby:

Does the term ‘assisted dying’ help public understanding? No, it doesn’t. In a UK poll conducted in 2021, when asked ‘What do you understand by the term “assisted dying”?’, 42 per cent of Brits polled thought it meant ‘Giving people who are dying the right to stop life-prolonging treatment’ – a right that they already have. When considering that the majority of Brits support the legalisation of ‘assisted dying’, it is useful to remember that much of what they support is already legal.

The campaign to legalise assisted dying often plays on people’s fears of how they and their relatives might die. Hence a typical campaigning video by Dignity in Dying, a leading UK-based assisted-dying campaign doctor to make it stop. He or she will be surrounded by relatives, who tearfully plead with hospital staff to end it. Many watching such short films will recall the death of a loved one and are genuinely horrified at the prospect that anyone else should have to suffer like that.Yuill acknowledges that the assisted suicide lobby sells a limited form of assisted suicide in order to gain support for legalization. But he examines the question of a life that is not worth living.

But how true is this scenario? Not very. In 2019, the CEO of Hospice UK, a charity that works with those experiencing death, dying and bereavement, publicly chastised Dignity in Dying for the ‘sensationalist and inaccurate’ portrayal of death in a video to accompany its ‘The Inescapable Truth’ campaign.

Dignity in Dying eventually removed that particular video but it is persisting with its scare tactics. It continues to claim that 17 people will suffer as they die every day. What it does not say is that an estimated 1,700 people die every day in the UK. That means, according to Dignity in Dying’s own statistics, that less than one per cent of the population will suffer as they die.

The charity, Humanists UK, however, argues that ‘we do not think that there is a strong moral case to limit assistance to terminally ill people alone…’. And campaign group My Death, My Decision also rejects restricting assisted suicide to the terminally ill. Yet even these organisations refrain from campaigning for the right of all competent adults who want to die to be assisted in their suicides. They just draw different lines between those whose lives are worth living and those whose are not.Yuill then examines the dark history of euthanasia in the twentieth century.

Moreover, virtually all assisted-dying advocates argue that doctors should ultimately be in charge of the process of deciding who is entitled to an assisted death. Even in Switzerland, where assisting a suicide is legal so long as there is no monetary interest involved, doctors are expected to facilitate suicides.

This is a serious problem. The decision as to whose life is no longer deemed worth living effectively rests with medical authorities or other representatives of the state. It is up to them to decide who should live and who should die.

Only in the early part of the 20th century did euthanasia proper come to the fore. In the United States, France, Great Britain and Germany, there were several unsuccessful attempts to legalise euthanasia. This pro-euthanasia campaign emerged against a political background increasingly dominated by eugenics. While ‘Social Darwinism’ implied that the fittest would survive if nature weeded out society’s losers, eugenics favoured active intervention to assist natural selection. As the German zoologist Robby Kossmann put it at the end of the 19th century, the state ‘must reach an even higher state of perfection, if the possibility exists in it, through the destruction of the less well-endowed individual… The state only has an interest in preserving the more excellent life at the expense of the less excellent.’He then writes about the German euthanasia movement.

In 1920 Karl Binding and Alfred Hoche published the pamphlet, Permitting the Destruction of Life Unworthy of Living. They argued that ‘there are indeed human lives in whose continued preservation all rational interest has permanently vanished’. Psychiatrist and neurologist Robert Gaupp – remembered for his principled defence of a man with Jewish associations in opposition to the Nuremberg Laws in 1935 – was referring to mentally disabled people when he said that it was time to remove ‘the burden of the parasites’Yuill explains that the Germans weren't the only ones promoting eugenic euthanasia.

Such views reached their grim culmination in the Nazis’ infamous T4 Aktion programme – an involuntary euthasia project responsible for an estimated 300,000 deaths of mentally and physically disabled patients between 1939 and 1945. Of course, no one should infer that these brutal killers bear any relation to today’s assisted-dying campaigners – who are, in general, sincerely compassionate in their motivations. But nor should we view the T4 Aktion programme as entirely distinct from the wider euthanasia movement.

In the US, supporters of euthanasia were equally vocal. ‘Our puny sentimentalism has caused us to forget that a human life is sacred only when it may be of some use to itself and to the world’, said the famous deaf, dumb and blind woman, Helen Keller. In the early years of the 20th century, Dr Ella K Dearborn cheerfully called for ‘euthanasia for the incurably ill, insane, criminals and degenerates’. And in the UK in 1931, Sir James Purves-Stewart, a physician at Westminster Hospital and future member of the Voluntary Euthanasia Legislation Society – the forerunner of Dignity in Dying – called on his countrymen to give euthanasia ‘most serious consideration’ because of ‘a grave menace to the future of the state’ and ‘race’. Another prominent ELS member, the psychiatrist and eugenicist, AF Tredgold, told the British Medical Journal that euthanasia should ‘also be extended to include incurable low-grade defectives. It is true that these would be incapable of consent, but their inclusion would appear to be a logical sequence of the proposal.’Yuill explains that euthanasia lost its appeal with knowledge of the Nazi euthanasia program. He explains that assisted suicide, as a concept, was not debated until the 1980's. Yuill continues:

Today, of course, the campaign for assisted dying is very different to that for euthanasia before the Second World War. But some of the same utilitarian concerns about certain people being a burden and a drain on resources persist just below the surface of today’s assisted-dying discourse. For example, in the Netherlands, where euthanasia and assisted suicide have been legal since 2001, mainstream political parties have expressed support for the Completed Life Initiative. Based on a 2010 campaign that boasted 117,000 supporters, the CLI promises euthanasia for those over the age of 74 who are ‘tired of life’. That this age group is also deemed the least productive in society should worry us all.Previous articles connected to Kevin Yuill (Link).

Then there is the widespread use of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), a measure of a person’s ability to carry out daily activities, free from pain and mental disturbance. This measure allows states to rationalise resources, especially medical resources, according to the ‘quality’ of the years a person might have left. Proponents of assisted suicide often employ QALY measurements to assert that the lives of people with certain conditions are not worth living. As two researchers argue, ‘denying access to assisted dying means that patients remain alive (against their wishes), and this can often necessitate considerable consumption of resources’

Legalising assisted dying should not be regarded as a simple step to bring relief to a very few. It is a huge step that will lead to some people’s lives – on physical, or sometimes mental grounds – being deemed not worth living. That is a dire and dangerous situation. There is wisdom yet in the famous old Christian precept, thou shalt not kill.

.jpg)

.jpg)