Testimony in strong opposition to SB 88 An Act Concerning Aid in Dying for Terminally Ill Patients

February 23, 2022 (Link to the testimony by Stephen Mendelsohn).

By Stephen Mendelsohn

Co-chairs and members of the Public Health Committee:

|

Stephen Mendolsohn

|

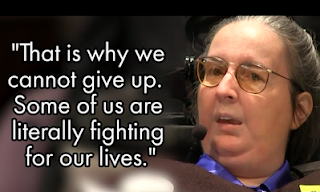

I am an autistic adult and one of the leaders of Second Thoughts Connecticut, a coalition of disabled people opposed to the legalization of assisted suicide. Second Thoughts Connecticut is a member of the Connecticut Suicide Advisory Board. Personally, I serve on the board of directors of Euthanasia Prevention Coalition-USA and previously served on the Connecticut MOLST Task Force.

We in the disability community have read this year’s bill as we have in previous years. We notice the changes from previous assisted suicide bills in an attempt to win over the opposition and get it passed. I am here to say that essentially nothing has changed. SB 88 is fatally flawed and should be rejected.

No amount of change in bill language can change the fact that some people will suffer prolonged and agonizing deaths from the experimental lethal drug cocktails, with some even regaining consciousness only to die of their terminal illness. Nothing can change the fact that the currently most widely used lethal compound, DDMA / DDMA-Ph, contains amitriptyline, which burns the throat. Medical science cannot guarantee the peaceful death proponents claim. If lethal injections administered for capital punishment have resulted in inhumane deaths, oral ingestion of lethal drug compounds is far more likely to do so. We may put our pets down without their consent and for bad reasons—because they are unwanted or have behavior problems—but at least we do not make them ingest these experimental lethal compounds and make them suffer even more in the process.

No change in language can change the deadly mix between assisted suicide and a broken health care and home care system. As the cheapest “treatment,” assisted suicide diminishes choice, and especially so for people of color, disabled people, and others who have been historically marginalized in our health care system.

No change in language can change the problem of misdiagnosis or the unreliability of terminal prognosis. Jeanette Hall, John Norton, and Rahamim Melamed-Cohen have outlived ostensibly terminal prognoses by decades. All three became staunch opponents of assisted suicide.

No change in language alters the fact that offering suicide prevention to most people while offering suicide assistance (redefined as “aid in dying”) to an ever-widening subset of disabled people is lethal disability discrimination.

The changes that have been made in the bill from previous years are ineffective and do nothing to protect against mistakes, coercion, and abuse. I will outline some of them and why this is so.

The definition of “terminal illness” in Section 1 (21) adds the words “... if the progression of such condition follows its typical course.” As Cathy Ludlum demonstrates in her powerful testimony, she still qualifies for lethal drugs under this definition. As Fabian Stahle notes, so do people with chronic conditions like insulin-dependent diabetes who reject treatment. So do people who have treatment denied by their insurance company or are otherwise unable to afford it.

Shockingly, even people with treatable anorexia who refuse nutrition have been deemed to be both “terminally ill” and “mentally competent” and thus eligible for assisted suicide. Without nutrition, the “typical course” for anorexia is death in under six months. The American Clinicians’ Academy on Medical Aid in Dying (ACAMAID) has a case report in which their “Ethics Consultation Service” stated,

If the patient’s eating disorder treating physician and evaluating psychiatrist agreed that she had a “terminal disease” and retained decision-making capacity, she would meet those requirements of the aid in dying statute in her jurisdiction.

At least one of ACAMAID’s physicians found it “ethically reasonable” to support assisted suicide in this particular case.

In testimony opposing an assisted suicide bill in Maryland, psychiatrist Dr. Angela Guarda, director of the Johns Hopkins Eating Disorders Program, shows just how destructive it can be to cut lives short by 60 years or more by offering assisted suicide for those deemed “terminal” for refusing nutrition (video starting at 3:37:00; unofficial transcript):

I treat people with anorexia nervosa, the most lethal psychiatric condition. Nearly every case can improve with expert care and many extremely ill patients make full recovery. Anorexia is challenging to treat because persons with this disorder are ambivalent towards and often avoid the treatment they most need: nutrition.

I had two recent cases “change their mind” and contact me from hospice where they were certified as terminally ill by their physician. Both improved dramatically with appropriate treatment and left hospital hopeful for their future. Under this bill they could be dead. Recovery feels out of reach to many with anorexia, to their exhausted family and to their doctor. And — these patients are often treated by general practitioners and avoid psychiatrists. Most doctors, — psychiatrists included, can recognize anorexia but have no training to treat it. Faced with a patient in intensive care who weighs 50 pounds is in kidney failure with unstable vital signs, all resulting from their anorexia, the attending physician may judge the patient terminal because they are unaware of, and don’t know, how to get her the treatment she needs — especially when she refuses it. And the starved patient could be influenced to view “aid in dying” as the best way out of an intolerable situation, or believe her family would be better off without her emotionally and financially.

The definition of “attending physician” in Section 1 (3) has been modified to exclude someone whose practice is “primarily comprised of evaluating, qualifying and prescribing or dispensing” the lethal drugs. This is apparently an attempt at discouraging doctor shopping. It will not work because anyone can just set up a 50-50 practice with half devoted to curative or palliative care and half to assisted suicide. Moreover, the limitation does not appear to be enforceable and there are no sanctions for setting up a practice primarily devoted to assisted suicide.

The definition of “competent” allows evaluations by social workers for capacity evaluations, and still allows someone else to speak for a patient with a communication disability.

Section 3 reverts to the 2015-2020 bills in requiring two written requests and disallowing heirs and other interested parties from being witnesses to the dispensing of the lethal prescription. Nonetheless, an heir can still bring two close friends to be witnesses to a pair of faxed-in requests and allows the examination to occur via telehealth. The attending and consulting physicians may have no idea that the patient is being pressured into dying faster by an abusive heir. Moreover, there is no required independent witness at the time the lethal drugs are ingested. Many people change their minds, yet all “safeguards” end once the prescription is dispensed.

Section 9 (6) (b) from previous bills, stating “The person signing the qualified patient's death certificate shall list the underlying terminal illness as the cause of death,” has been removed from SB 88. In no way does this mean that death certificates will not continue to be falsified. Previous bills demonstrate clear intent to do so. In Oregon this language is not in statute but is in regulations, and that is certain to be the case in Connecticut. The only way to correct this is to specifically include language similar to Oklahoma’s Death Certificate Accuracy Act, §63-1-316b. It states in part:

A certifier completing cause of death on a certificate of death who knows that a lethal drug, overdose or other means of assisting suicide within the meaning of Sections 3141.2 through 3141.4 of this title caused or contributed to the death, shall list that means among the chain of events under cause of death or list it in the box that describes how the injury occurred. If such means is in the chain of events under or in the box that describes how the injury occurred, the certifier shall indicate "suicide" as the manner of death.

A certifier who knowingly omits to list a lethal agent or improperly states manner of death in violation of subsection E of Section 1-317 of this title shall be deemed to have engaged in unprofessional conduct as described in paragraph 8 of Section 509 of Title 59 of the Oklahoma Statutes.

Moreover, the “accordance” language in Section 14 (c) and (d) of SB 88 also mandates falsification of death certificates. According to the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, death certificates in Connecticut are required to list the manner of death as either “homicide,” “suicide,” “accidental,” “natural,” “therapeutic complication,” or “undetermined.” The “accordance” language rules out homicide and suicide as a matter of law, and “accidental,” “therapeutic complication,” and “undetermined” are clearly ruled out as the manner of death is both intentional and of known cause. Thus as in other states, the death will be deemed “natural,” even if it was unnaturally caused by an intentional overdose of lethal drugs. This would interfere with a potential murder prosecution no less than the removed Section 9 (6) (b) from previous bills.

This “accordance” language would also interfere with our state’s suicide prevention plan, which calls this act suicide and notes the intersection between assisted suicide and suicide prevention, particularly with regard to suicide prevention for disabled people (pp. 57-59).

Beyond the failure of any changes to the bill language to protect against mistakes, coercion, and abuse, there is the issue of expansion. We only need to look at what Compassion & Choices and other proponents are saying, and the bills and lawsuits they have been pushing in other states. We can all remember when Compassion & Choices’ president emerita Barbara Coombs Lee came to Hartford in October 2014 declaring support for assisted suicide for people with dementia and cognitive disabilities unable to consent; in her words, “It is an issue for another day but is no less compelling.”

We can also look at recent expansion legislation and court cases being pushed by Compassion & Choices in other states, particularly those in states that already have legalized assisted suicide, including Oregon, Washington, California, Vermont, Hawai‘i, and New Mexico. Bills have provisions that would dramatically shorten and/or waive the mandatory waiting period, allow APRNs and PAs to prescribe lethal drugs, waive the requirement for a second doctor to confirm the ostensibly terminal diagnosis, allow almost anyone who does counseling for a fee to qualify in the rare case that the patient is referred for a mental health evaluation, allow mail-order delivery of lethal overdoses, and compel objecting providers to refer patients to other providers who will dispense lethal prescriptions.

This last provision, enacted last year as California SB 380, is a threat to patient safety, as noted by the example of Jeanette Hall, who sought to die under Oregon’s law but was persuaded by her doctor to accept cancer treatment and is still alive more than 20 years later. Under a “do or refer” regime supported by Compassion & Choices, people like Jeanette Hall would have their lives cut short by years or even decades as ethical doctors will be forbidden to use their professional judgment to encourage their suicide-minded patients to seek lifesaving treatment.

Compassion & Choices and other assisted suicide proponents are already active in attempting to strike down the residency requirement in Oregon and the self-administration requirement in California.

So when Compassion & Choices’ president Kim Callinan testifies about all of the “safeguards” in SB 88, please remember she is working diligently to gut these same provisions in the aforementioned states that have already enacted this legislation.

Moreover, once the concept of certain people having a right to assistance with their suicides to end their suffering is codified into law, there is no limiting principle to prevent it from being extended to other disabled people who also may claim to be suffering. If SB 88 were enacted, further expansion will move into the hands of judges. While we in the disability-rights community view legalizing assisted suicide as a violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act and the disability equal protection clause (Article XXI, amending Article V) of the Connecticut Constitution—people with certain disabilities are thus denied the benefit of suicide prevention services—judges could easily use both of these provisions to require extending the “benefit” of this “end of life option” to other disabled people. The limitations of “six months,” “terminally ill,” “mentally competent,” and “self-administer” in SB 88 all discriminate on the basis of disability. Indeed, back in 1999, former Deputy Attorney General of Oregon David Schuman wrote this response to state senator Neil Bryant regarding the issue of self-administration:

“The Death with Dignity Act does not, on its face and in so many words, discriminate against persons who are unable to self-administer medication. Nonetheless, it would have that effect....It therefore seems logical to conclude that persons who are unable to self-medicate will be denied access to a ‘death with dignity’ in disproportionate numbers. Thus, the Act would be treated by courts as though it explicitly denied the ‘benefit’ of a ‘death with dignity’ to disabled people....”

Indeed, the Connecticut Supreme Court’s ruling in State v. Santiago, striking down a prospective repeal of the death penalty in favor of full repeal, shows how our courts can expand laws beyond the intent of this legislature using equal protection grounds. The same principle is at work with SB 88, which gives suicide assistance to some while others get suicide prevention, and the arbitrary difference is what disability they have.

So what about the person with ALS who has a six month prognosis, but has lost the ability to self-administer? What about the person with Parkinson’s disease, who will have tremors for years before dying? What about people with communication disabilities who may not be able to make the request on their own? What about Grandma with dementia, or the person with a severe psychiatric disability? Once the door to assisted suicide is pried open, Compassion & Choices will seek to open it further through the courts, going from six months terminal to one year, to perhaps five years; from assisted suicide to euthanasia; and from euthanasia for terminal illness, to chronic illness, to mental suffering. This is how we go down the same road as Canada, which has enacted Bill C-7 to allow euthanasia even for non-physical conditions, and where hospitals routinely deny treatment to disabled people while offering euthanasia instead. For Compassion & Choices, these are merely issues for another day, and for them, no less compelling.

Legislators and the public should not be fooled by a privileged lobby that seeks to sell suicide as a solution to their own disability-phobia. We should follow the recommendations of the National Council on Disability’s report, “The Danger of Assisted Suicide Laws,” and reject codifying lethal and systemic disability discrimination into law.