Alex Schadenberg

Executive Director, Euthanasia Prevention Coalition

Link to the study

The study examines the number of deaths, the reported reasons for seeking death, and the application of the law. It uncovers significant problems with the Oregon assisted suicide data.

Assisted suicide rate

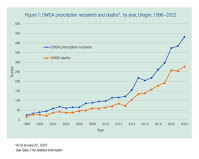

Over 25 years, 2,454 individuals have died from an assisted death. In 1998, 24 prescriptions were written for PAS drugs and 16 patients died from ingesting these drugs. On average, the number of PAS drugs prescribed under the legislation increased by 13% each year and the number of patients who died by ingesting these drugs by 16% annually. In 2022, 431 prescriptions were written, and 278 patients died by PAS. The proportion of deaths following ingestion of prescribed drugs compared with the prescriptions written increased slightly, from an average of 58% in the first decade (1998–2007) to 66% in the second decade (2008–2017), following which it has been stable at an average of 67% over the last 5 years.

The study examined the increase in assisted suicide deaths and indicates that the numbers have increased on a nearly steady basis.

End-of-life concerns for participants

In the first decade of legislation of PAS in Oregon, an average of 65% of participants were privately insured. Since 2008, this proportion has reversed; in 2022, 20.5% of those who died by PAS held private health insurance, while the majority (79.5%) had government insurance through Medicare or Medicaid.

The percentage of PAS patients who cited being a burden on family and friends increased during the time period. The number of patients reporting financial concerns about treatment as an end-of-life concern is low, though there is evidence of an increase over the time period (up to 8.4% in 2021). In the first 5 years of PAS, an average of 30% of participants were concerned about being a burden. Since 2017, this concern has been cited by around half of those who die by PAS (46% in 2022).

Patient eligibility and approval process

Eligibility under the DWDA requires that patients have been diagnosed with an illness that will reasonably lead to death within 6 months. Cancer remains the main diagnosis of PAS patients, though the proportion has reduced over the time period from an average of 80% in the first 5 years to 64% in 2022. In 2022, 109 patients (25% of prescription recipients) were granted an exemption from the usual 15-day reflection period on the basis that they were terminal. Since 2010, patients with a range of non-cancer diagnoses have received PAS including non-terminal illnesses such arthritis, arteritis, complications from a fall, hernia, sclerosis, ‘stenosis’ and anorexia nervosa.

Referrals for psychiatric evaluation have declined as a percentage of assisted deaths. In the first 3 years after enactment (1998–2000), a psychiatric assessment was sought in an average of 28% of cases. By 2003 this had dropped to 5%, and in 2022, 1% of patients who died from PAS underwent psychiatric evaluation. Since 2010 there has been a reduction in both the median duration of the physician–patient relationship and the time from the first request to death. In 2010 the median physician–patient duration was 18 weeks, dropping to 5 weeks in 2022. The time from the first request to death had reduced from 9.1 weeks in 2010 to 4.3 weeks in 2022.

Assisted suicide drugs

From 1998 to 2015, the most common drugs used for PAS were barbiturates, with phenobarbital, secobarbital or pentobarbital used alone. It is now standard for drug combinations to be used, with different combinations being used in the last 8 years, although the dose of each constituent drug is not reported: 2015–2022: DDMAP (diazepam, digoxin, morphine sulfate and propranolol); 2018–2022: DDMA (diazepam, digoxin, morphine sulfate and amitriptyline); 2019–2022: DDMA-Ph (DDMA plus phenobarbital). The 2022 report states that the combinations have resulted in longer times from ingestion to death (3 mins to 68 hours; median 52 min), compared with an aggregate range of 1–104 hours, with a median of 30 min over the 25 years. The number of prescriptions per doctor has increased from an average of 1.6/doctor in the first 5 years to 1998, to an average of 2.7/doctor between 2018 to 2022.

Stated complications following the ingestion of PAS drugs have included difficulty in ingesting drugs, regurgitation, seizures, regaining consciousness and ‘other’ complications that are not described. Complications associated with PAS drugs were reported in an average of 11% between 2010 and 2022, with a peak of 14.8% in 2015. In 2022 complications were identified in 6% of patients, though data on complications was missing in 206 patients (74%). Over the last 25 years, nine patients have regained consciousness.

In Oregon in 2022, 46% of patients did not take their prescriptions. Of these, 84 died of other causes. In 101 patients the ingestion status was not known, only that 43 died. In 58 patients the status of death and ingestion was unknown at the time of the report.

Demographics for assisted suicide deaths

Patients’ end-of-life concerns are reported across eight categories, allowing several concerns to be reported. It is unclear whether these are the patients’ direct reports or those reported retrospectively by the clinician. Concerns cited about ‘losing autonomy’ (91%) and ‘less able to enjoy activities making life enjoyable’ (90%) remain dominant across each year. Over time, there has been an increase in the proportion of patients including concern about being a burden on their caregivers and in those expressing financial concerns about their treatment.

The OHA reports reveal a higher uptake of PAS among those with higher educational levels, but income levels are not given. In Belgium, lower education levels are associated with less intense pain and symptom alleviation, but income was not examined. It is possible to have a high education attainment, but be on a low income. Other vulnerabilities are becoming clearer. For example, patients with mental health issues asking for assisted death in the Netherlands were more likely than the general population to be female, single, of lower educational background and with a history of sexual abuse. In Switzerland, although PAS was associated with higher socioeconomic status, PAS was also more common in females and situations indicating vulnerability such as living alone or being divorced. In 2018 an Oregon Health Statistics official acknowledged that they will accept PAS requests if the patient has refused treatment for financial reasons. Although socioeconomic data already exist for some medical conditions in Oregon, these have not been linked to PAS requests.

Recently the cost benefit to individuals and to society of assisted deaths have been discussed in relation to quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). Economic arguments in support of assisted deaths include the avoidance of possible negative quality of life of the patient, and freeing up healthcare resources for others including organs for transplantation. ... A 2019, a US Gallup poll found a quarter of respondents reported they or a family member had been put off treatment for a serious medical condition because of the cost. In 2020, 31.6 million people in the USA (9.7% of the population) had no medical insurance.

There is a dearth of studies linking socioeconomic vulnerability and PAS data. The change in health funding in Oregon is unlikely to be due to a lag in data since the change to state funding started 15 years ago. Detailed studies are needed to explain the marked change in medical funding for PAS patients in Oregon.

Doctor-patient relationship

The very low referral rate for psychiatric evaluation could be the result of an efficient screening process. However, there is evidence that depression and existential issues such as hopelessness can influence a wish to die and are commonly missed by doctors. Loneliness is known to be associated with depression which, in turn, increases the likelihood of a wish to die. Elder abuse, which can be difficult to identify, has become a major public health issue in both the USA and the UK, and in Oregon, elevated rates of non-assisted suicide have been observed in older women. The OHA data show that the duration of the patient–physician relationship is now almost the same as the time from first request to the assisted death. This steady reduction in the physician–patient relationship in Oregon may have made it more difficult to identify treatable factors influencing the wish to die, but there is a lack of recent data on how many Oregon PAS patients have a treatable depression.

Assisted suicide prescriptions

In 2022, 146 Oregon physicians wrote prescriptions, one of whom wrote 51 prescriptions. These doctors represent <0.9% of the 16 621 active medical licensees. There is a lack of data on whether this results in difficulty seeking a prescriber, whether those writing few prescriptions have limited experience of assessing eligibility, and what happens to the nearly half of prescribed PAS drugs that are unused.

Oregon does not provide data on what proportion of PAS deaths take a particularly long time to die. Washington reported that in 2021 31% of patients died within 30 min and 16% took more than 2 hours to die. Although the time was unknown in 17.9%, the Washington reports provide no information on the drugs used and whether they were changed to achieve shorter dying times.

The Oregon OHA reports show that complications affect one in nine patients on average, although Oregon does not include prolonged deaths or patients who regained consciousness in their complication percentages. A peak in the complication rate (14.8%) in 2015 coincides with a switch to drug combinations. However, the true incidence of complications is unknown since in 2022 data on complications were missing in 206/278 (74%) of assisted deaths.

Expansion of assisted suicide in Oregon

Oregon is often given as an example of stable assisted dying legislation. In January 2020 Oregon waived the statutory 15-day waiting period for patients estimated to have a shorter prognosis, resulting in a quarter being granted this exemption in 2022. In 2022, 16 patients (6%) outlived their 6-month prognosis following prescription of PAS drugs, but there is no detail on how many had treatable conditions or had been misdiagnosed. In 2017 the OHA confirmed that incurable terminal illness is when there is an affirmative response to the question ‘should the disease be allowed to take its course, absent further treatment, is the patient likely to die within 6 months?’. Any patient has the right to refuse treatment, but it is concerning that there is a lack of data on why they refused treatment and how they were advised and counselled.

For example, in 2021 anorexia nervosa was one of the diagnoses listed, but without any details of comorbidities, if this was an isolated case, or whether the clinician misjudged the prognosis or misapplied the law. Anorexia nervosa in any young adult with capacity is terminal if it persists, but it can be challenging to determine the point at which treatment cannot succeed.

In 2022 a federal lawsuit brought by an Oregon doctor forced Oregon to allow non-residents to access PAS.

Involvement with palliative care

In 2022, 92% of people requesting PAS were enrolled in hospice care and the mean for 1998–2020 was 90.8%. However, there are no data on what services were provided and the term ‘palliative care’ is not mentioned in any reports, nor the duration of enrolment.

...The lack of information on whether Oregon PAS patients are receiving care from specialist, interdisciplinary palliative care, or a single, non-specialist practitioner makes it difficult to evaluate whether adequate palliative care was received before PAS in Oregon.

Limitations that exist in examining Oregon assisted suicide data

We limited our analysis to descriptive trends. Retrospective analyses for PAS in Oregon are limited to the content of published reports since Oregon destroys all source records 1 year after each annual report, making verification of data impossible. In addition, missing data for some variables (eg, complications) is high and Oregon does not collect data on how or why PAS decisions were made, pre-evaluation or post-mortem review of cases and the details of rejected requests.

We have found no evidence of the completeness or otherwise of the notification process. As there is no prescription monitoring service in Oregon, it is not possible to triangulate data on prescribed lethal drugs, their ingestion and disposal of unused drugs. As physicians are not required to be present when lethal drugs are taken, data provided for the reports depends on information from whoever was present and from provider questionnaires.

Conclusion

Oregon is often cited as a stable example of assisted dying legislation. Despite Oregon producing detailed and regular post-death reports of value, there are considerable gaps in the data across US states. Most importantly, there is no monitoring in any form of the quality of the consultation in which the decision was made to prescribe lethal drugs. Although population mortality follow-back studies have been used to study end-of-life care, these have limitations. Detailed, prospective studies that include socioeconomic and clinical information are essential to understand fully the changes seen in Oregon PAS data.More articles on the Oregon assisted suicide law.

No comments:

Post a Comment